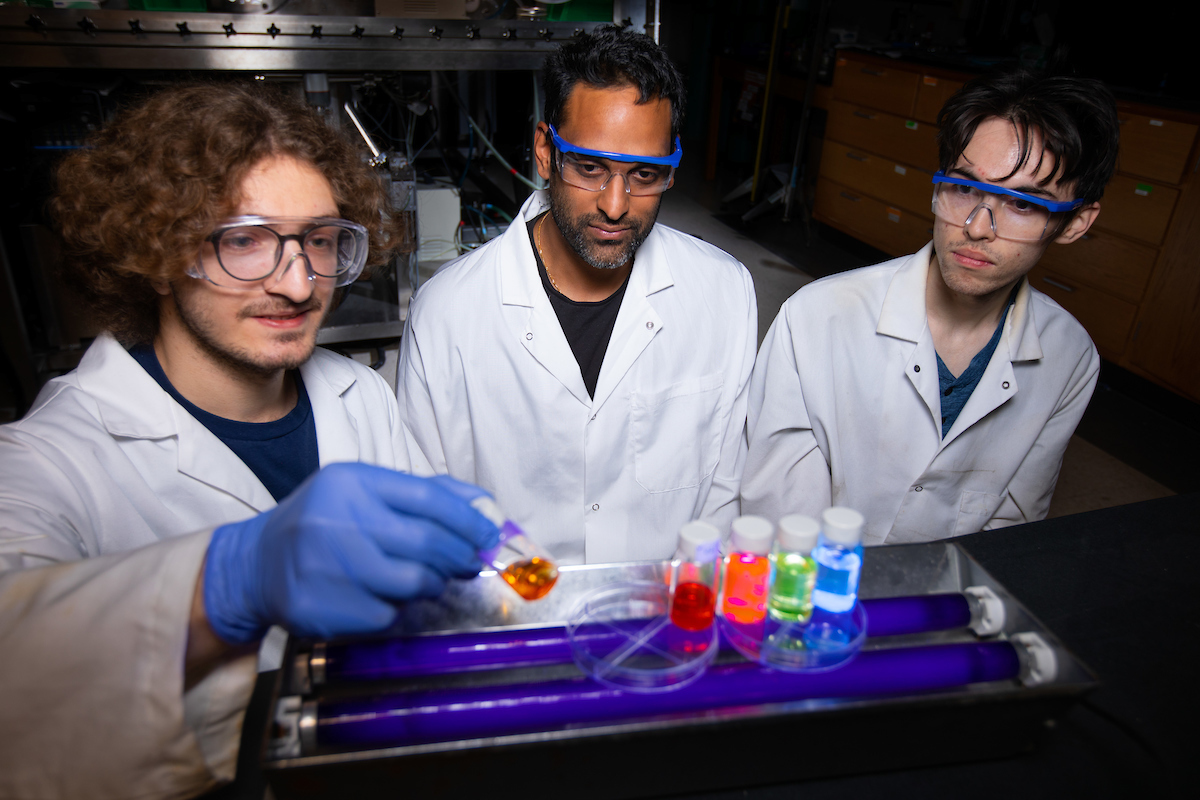

Matthew Panthani, center, and doctoral students Maharram Jabrayilov, left, and Andrew Tan, observe vials of silicon quantum dots, nanoparticles with properties such as light and color that are determined by their sizes. The discovery and development of quantum dots won the 2023 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for scientists in New York and Boston. Larger photo. Photos by Christopher Gannon/Iowa State University.

AMES, Iowa – A Google Cloud video takes you inside a company data center in

southwest Iowa’s Council Bluffs.

There you are, in the middle of a long, industrial corridor. You slowly move past rack after rack after rack of the computer servers that are, Google says, “helping to keep the internet humming 24/7.”

Part of that hum is the power that keeps those data centers up and running.

“Think about when you use your computer,” said Matthew Panthani, an associate professor of chemical and biological engineering at Iowa State University. “It gets hot, right? When the processor performs calculations, it’s using energy. That’s producing heat, which is wasted energy.”

And now, with artificial intelligence tools available to everyone, “there’s a huge spike of energy consumption in the U.S.,” Panthani said. “How can we solve this problem?”

Photons on the job

Panthani is right about spiking energy consumption.

Data centers could use up to 9% of U.S. electricity generation by 2030 – more than double current consumption, according to a study released in May by EPRI, an independent, non-profit energy research and development organization.

The study says the move to artificial intelligence tools is one reason for the spike. Artificial intelligence searches require about ten times more electricity than a traditional internet search. And AI-generated photos, videos and music require even more power.

Panthani’s approach to a solution isn’t a new idea, but it’s been a challenging one: “Use integrated photonics. Let’s use light to transmit data on chips instead of electricity.”

“Fiber optics has already solved this on a global scale,” he said. “It’s the same concept of moving data with light. It’s efficient and fast. But it hasn’t happened with chips yet.”

That’s because there’s a materials problem, Panthani said. The material of choice for semiconductors is silicon, which doesn’t emit light.

Arranging the atoms just so

Panthani’s lab has been working on new materials for integrated photonic circuits since 2017. The lab’s current focus is to develop atom-thin sheets of a silicon-germanium alloy. Those sheets can be stacked in layers separated by alkali metal ions such as lithium or salts, creating layered semiconductors.

A new, three-year, $552,000 grant from the National Science Foundation will support Panthani’s latest work to develop the semiconductors. Three doctoral students – Andrew Tan, Abhishek Chaudhari and Maharram Jabrayilov – will contribute to the effort. The grant will also bring high school teachers into the lab during the summer months, helping them improve their teaching by learning more about scientific research.

In addition to synthesizing the semiconductors “with precise control over the arrangement of atoms in the material,” a project summary says the researchers will study how structure and chemistry influences the semiconductors’ optical and electronic properties and they’ll determine their thermal and environmental stability. All of that would advance basic knowledge in materials chemistry, nanotechnology and semiconductors.

Basically, Panthani said, the semiconductors would emit light “and we want to understand how they could emit light better.”

Achieving that could have real-world applications and implications.

“Integrated photonic circuits have the potential to result in computers and mobile phones that use much less electricity and operate faster,” the summary says.

And maybe one day it won’t take nearly as much power and heat to keep data centers around Iowa – and the world – humming along 24/7.

Contacts

Matthew Panthani, Chemical and Biological Engineering, 515-294-1736, panthani@iastate.edu

Mike Krapfl, News Service, 515-294-4917, mkrapfl@iastate.edu

Quote

With artificial intelligence tools available to everyone, “there’s a huge spike of energy consumption in the U.S. How can we solve this problem?”

Matthew Panthani, Chemical and Biological Engineering

Quick look

Matthew Panthani and his research group are developing new materials that allow semiconductors to emit light. The resulting integrated photonic circuits could make computers, phones and other electronics faster and more energy efficient. The National Science Foundation is supporting the work with a $552,000 grant.

Matthew Panthani